Five Prescriptions for Simplifying Science Policy

Some thoughts on the National Academies’ latest report on reforming federal science.

The world of research has gone berserk/

Too much paperwork.

- Bob Dylan, from the song Nettie Moore (2006)

I don’t need to tell you that the bureaucracy involved in securing federal funding and complying with regulations hampers science. In addition to being slow, the federal science enterprise is very big — so big that a report of 53 options for improving science processes only scratches the surface of what needs to be done. In 2025, the National Academies presented that menu in their Simplifying Research Regulations and Policies: Optimizing American Science, selecting options for their likely impact, and taking into consideration the Trump administration’s interest in reducing regulation.

I’m a pragmatist when it comes to improving science.1 I know the recommended reforms will not revolutionize the American research enterprise; large-scale changes require political decisions rather than technocratic tweaks. But the National Academies’ recommendations can remove red tape and meaningfully simplify federally funded science. There’s value in tractable, tactical solutions. We should be ready for major windows of opportunity — new institutional structures, Manhattan Projects, moonshots — and seize them. But if we fail to improve coordination and cut back bureaucratic sludge, the government will ossify in the meanwhile.

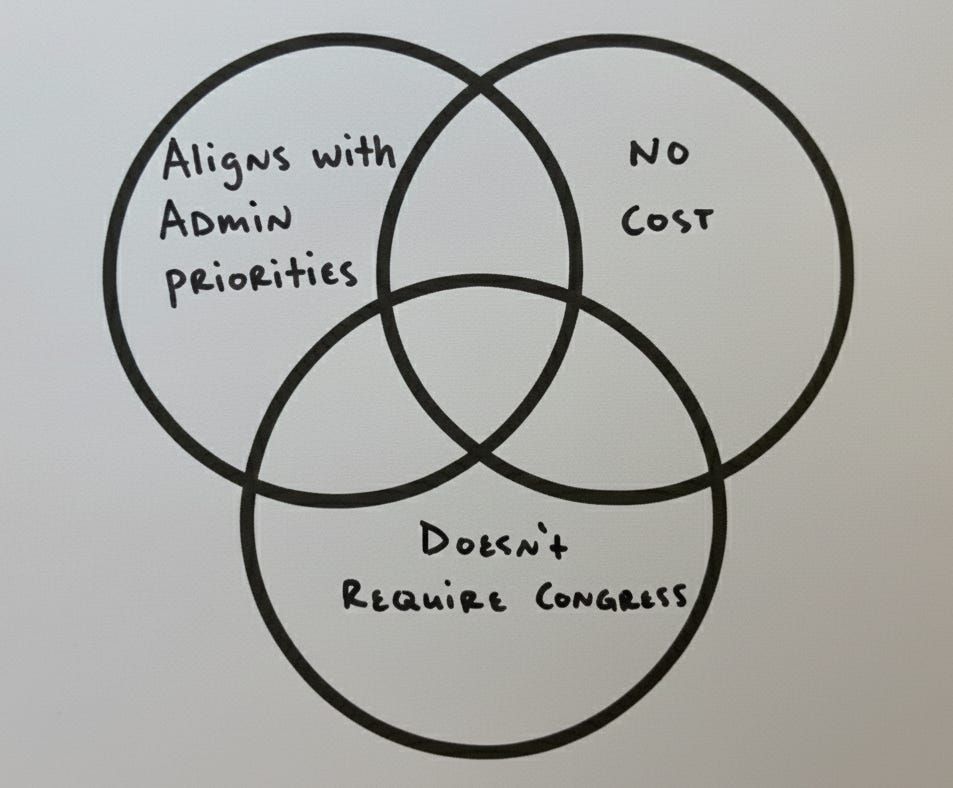

All 53 of the report’s prescriptions are worth considering, but a few stand out to me as most tractable and promising. My heuristic here was identifying the recommendations that don’t cost money (staff time is OK), broadly align with the current administration’s priorities for science, and don’t require congressional action.

Why these three filters?

Finding unobligated funding is difficult and we can’t count on new congressional appropriations.

You’re most likely to succeed by aligning policy advice with a sitting administration’s priorities. This is doubly important when regulatory reform is highly centralized in the White House, as it is now.2

Congress is slow in the best of times, and is particularly dysfunctional now. In the current climate, it’s more efficient to focus on reforms that don’t require legislative changes.

Selecting five options means that I didn’t discuss the other 48. Some of my assumptions may diverge from those of the report authors (e.g., I think congressional action is unlikely right now). I’ve also left out ideas I wasn’t dazzled by or that were hyperspecific or esoteric — there’s a lot of content on animal testing, which is important, but a bit niche.

Here are the five interventions I suspect would be most effective, ordered by appearance in the report (though the first is my top priority).3

Problem: Federal grant processes are inconsistent and burdensome

Option 1.1: Introduce a federal-wide, two-stage pre-award process

In a typical research grant process, scientists submit a comprehensive application (sometimes upwards of 30 pages), which is then reviewed by a panel of external experts. The National Academies report recommends a two-stage process instead, which would allow scientists to receive feedback on their ideas without the effort of a full application.

In a two-stage pre-award process, applicants submit a brief letter of intent (LOI) and agencies invite top applicants to submit a full application. The report states that in this model, “subject-specific review panels would evaluate the LOIs to assess the merit of the proposed research.” This could be a group of agency subject matter experts, obviating the need for external experts’ time and effort. This approach both lowers the barrier to submitting applications (potentially giving a boost to early career scientists) and reduces the burden on external review panels.

Select grants and contracts, such as the Department of Energy’s Small Business programs and DARPA activities, already use two-stage review, but is uncommon across the government. Agencies’ reasons for hesitating to implement it are legitimate — I recently spoke with some agency science leaders who were concerned that two-stage review might lead to an explosion in the number of LOIs (since the bar to submitting would be lower), and that researchers might object to being rejected based on just a brief submission. Other barriers might include insufficient staffing or in-house expertise to modify existing processes or review LOIs.

I don’t want to downplay these potential challenges. However evidence suggests that, with adequate staffing, empowered program officers can effectively select projects for quality. And an explosion of LOIs may be a positive signal that more early-career scientists or researchers from non-elite institutions are applying.

There are ways to manage potential implementation challenges. Agencies should consider creative strategies to manage an influx of LOIs, such as by limiting the number of LOIs that each applicant can submit annually. As for complaints about rejections based on mere LOIs: while this advice is easier to give than to take, agency staff should not be afraid to offend applicants. The applicant will learn something important about their alignment with agency goals or find ways to improve their idea, and — because the barrier to submitting an LOI is low — they can always make changes and submit again.

Implementing two-stage review is likely the highest-impact reform proposed in the report. If implemented well, with empowered program officers and a clear process, two-stage review can make it easier to pitch a project to funding agencies and reduce the number of full applications that need to be written and reviewed.

Problem: Financial conflict of interest (FCOI) requirements are inconsistent

Option 3.1: Create uniform “conflict of interest in research” policy

Federal science agencies currently have varying disclosure policies for potential financial conflicts of interest (FCOI). Two of the most influential are the National Science Foundation (NSF) policy and the Public Health Service (PHS) policy (which NIH uses). The PHS policy is stricter than the NSF policy, requiring additional reporting and training, and sets a lower monetary threshold for conflicts of interest (i.e., the amount of money the applicant can have received from another entity with an interest in the outcomes of the research).

A consistent policy would simplify compliance while still ensuring the government is collecting the data it needs on potential conflicts; the report recommends that the government go with NSF’s. One potential hitch is that Congress wants substantial oversight on science funding; a 2020 report critiqued the NSF policy for being more permissive.

The National Academies report authors don’t think the stricter PHS regulations are more effective than the NSF rules. And a study showed that when PHS reduced the threshold for reporting from $10,000 to $5,000 in 2011, it increased compliance costs, but only surfaced 13% more potential FCOIs.4 At the very least, the government should conduct a cost-benefit analysis of the PHS policy to determine whether the additional data collected and potential FCOIs avoided is worth the costs of compliance.

Problem: Research security protocols are overly complicated

Option 4.1: Implement the National Security Presidential Memorandum-33 (NSPM-33) common disclosure forms and disclosure table without deviation as the primary means to identify and address Conflicts of Commitment (COCs) and develop federal-wide FAQs via the interagency working group; in addition, use the Science Experts Network Curriculum Vitae (SciENcv) system, persistent identifiers (PIDs), and application programming interfaces (APIs) across research funding agencies

Long title, but a straightforward idea — make it easier for researchers to comply with Presidential Memorandum 33, which requires research institutions to report to the government how they secure R&D against foreign interference. Science agencies have been gradually adopting a common research security biographical information form since it was finalized by the White House National Science and Technology Council (NSTC) in 2023 (with NIH expected to adopt it in early 2026). However, agencies such as NASA have already started adding on their own requirements; hence the report’s “without deviation” language. One can imagine a situation where an agency needs specific information for research security purposes, and no doubt agency staff will be tempted to view their situation as unique. But NSTC developed the common forms based on practices agreed upon by the interagency, and — at least in the case of NASA — the departures from the standard form seem more administrative than security-related.

Cole Donovan, who was OSTP Assistant Director for Research Security in the Biden Administration, agrees that agencies tend to view their circumstances as unique, but notes that for sensitive research there are other rules designed to prevent data being disclosed to other governments. So in nearly all cases, going beyond the NSPM-33 common forms would be unnecessary. Donovan tells me, “At a minimum, disclosure and security program requirements should be calibrated to not exceed those of agencies whose primary mission involves providing direct support to the warfighter or intelligence community, absent extremely strong, evidence-based justification.” In other words, some civilian agencies are putting in place research security protocols more complicated than military or intelligence agencies’ protocols, and that doesn’t make any sense.

OSTP, which issues the guidance for form use, should encourage uptake of the common disclosure forms and discourage agencies from adding their own requirements. Research security is important, but it is burdensome (many of the regulations noted in the COGR chart above relate to research security) and the government should do what it can to reduce costly and unnecessary burdens.

Problem: Regulations for research involving biological agents are complex and overlapping

Option 5.2: Simplify and harmonize current NIH, USDA, CDC guidelines, and exempt low-risk activities.

Right now, there are overlapping regulations, guidelines, and policies from federal agencies on managing the use of biological agents and toxins in research. This is onerous for research institutions that work with multiple agencies and suboptimal for risk management. The complexity and decentralized nature of the system make it hard for the government to track and oversee use of biological agents and toxins, which the report cites as having “potential national security implications” or “significant societal consequences.”

The report suggests that the NIH review its guidance and identify opportunities for simplifying it and harmonizing with other agencies’ policies, with the optimal option being broad adoption of the NIH policy. The report goes on to recommend a seemingly easy win, by government standards: exempting low-risk biological research from onerous oversight.5

American scientists conduct some legitimately high-risk biological research (on anthrax, tuberculosis, etc.), and oversight should focus on that.

Problem: Inadequate regulatory adaptation to evolving research methods and technologies

Option 6.14: Establish a cross-agency initiative to align and consolidate guidance on emerging research methods.

Human subjects research has changed substantially in recent years and will continue evolving with new technology (the report cites “decentralized trials, use of digital health tools, and AI-driven protocols”). Federal regulations struggle to keep up with the changes, but now is the time to bring human subjects regulations up to date. The report suggests that HHS lead this process given its extensive human subjects research record.

Consolidating guidance may be difficult since HHS recently canceled the Secretary’s Advisory Committee on Human Research Protections, which was the primary entity coordinating human subjects regulations. It is unclear how HHS is making decisions about human subjects review in the absence of this committee; OSTP should work with HHS to lead a cross-governmental effort to update guidance.

Notably, the National Academies recommendation doesn’t define an intended outcome, and “establishing a cross-agency initiative” is just a starting point. But with technology advancing at a blistering pace and scientists leveraging it in novel ways, the federal government can’t be asleep at the regulatory wheel.

Cutting bureaucracy sometimes requires more bureaucrats

The National Academies report is largely about improving coordination: 22 of the report’s 53 recommendations focus on centralizing processes or establishing clear ownership.6 Done well, centralization means fewer processes for scientists to navigate, cutting administrative burden and freeing them to focus on research.

But harmonizing requirements and processes requires accounting for different agency needs and mandates, and demands effort by agency staff without immediately obvious benefits. Harmonization efforts are labor-intensive and require sustained commitment from political appointees and career staff alike. But the government lost around 335,000 staff in 2025 and, in some agencies, sparse political leadership makes change even harder.

Hiring and empowering the right people is crucial for reforming science. While current leadership within individual agencies can advance some of the report’s reforms, more meaningful change will require the Trump Administration prioritizing staffing up departments and agencies like OSTP, HHS, and NSF to coordinate across the federal science enterprise. This will entail short-run investment, is but well worth it to de-sludge American science.

It’s possible I’m a Centrist Dad.

Much of this regulatory power is centralized in the Office of Management and Budget (OMB). OMB head Russ Vought described his vision for a muscular OMB in a Statecraft interview last summer.

A note on numbering — the report is divided into seven sections, each focusing on a specific topic (grants and proposals, research misconduct, etc.), with multiple options for each topic (1.1, 1.2, etc.). I have kept the report’s numbering convention for easier cross-referencing.

Because the PHS threshold was not set to rise with inflation, it’s also now meaningfully lower than it was after the change in 2011. Five thousand dollars in 2025 would have been worth around $3,500 in 2011.

The Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories manual (the authoritative HHS document) lists eukaryotic cell cultures, particularly those not involving human or primate cells, as an example of low-risk activity. A eukaryote is a “cell or organism that possesses a clearly defined nucleus.” Eukaryotic cell cultures involve growing these complex cells in a controlled, laboratory environment.

I take centralization to mean things like creating a standard form, standardizing a process, appointing a lead agency, or improving coordination on a decentralized issue.

Thanks for covering this report!

Much of it is about consolidating multiple rulesets into one ruleset. However, I agree with you that experimenting with new institutional structures is essential. Will we lose some of that freedom to experiment when we force harmonization? e.g. How would we know if PHS-level or NSF-level policies are necessary if we hadn't already tried them both?