Do Not Surrender to the Tech Tree

A defense of human agency in a techno-deterministic world

Editor’s note: This essay is not about science policy per se. But its focus — the extent to which human decisions can shape the future of technology — is crucial to what happens in science. I’ve noticed that people who care about science and those who think about the future of AI don’t always communicate. They have different assumptions about the future and beliefs about what drives progress.

Tao initially posted part of this piece as a tweet. This longer essay defends a strong form of technological determinism and suggests how we can still positively steer technological development during critical windows of opportunity. I learned a lot editing this piece, and it helped me to better define what I believe about progress. I hope it challenges and provokes you (and that you enjoy it — it’s a good read).

In defense of technological determinism

The human experience is defined by technology. People in New York, Beijing, Abu Dhabi, and Vienna all wake to their phone’s alarm, turn on their electrical lights, use a modern bathroom with running water, get dressed in similar clothes, commute to similar workplaces in cars or trains powered by combustion engines or electric motors, and so on. We consume similar foods, use similar apps on our phones, consume more content in a week than our ancestors might have in a lifetime, are born in similar hospitals, and die from similar diseases. For all the important differences between the West’s liberal democratic order and the authoritarian rule in China, Russia, and other countries, our lives in rich metropolises have much more in common with one another than with those of the feudal or pre-agricultural societies of the past, anywhere in the world. Why did our societies converge in the same idiosyncratic ways?

Technological determinism is a two-pronged worldview that offers a plausible explanation. Its first axiom is that technology is a critical determinant of human experience, societal structures, and even culture. It posits technological development (or lack thereof) as a core driver of our lives becoming so similar across the “developed” world. This could also explain why, for example, societies that have been cut off from technological progress, like the Sentinelese, have ways of life similar to those of every other technologically primitive society around the world, be it contemporary or ancient.1

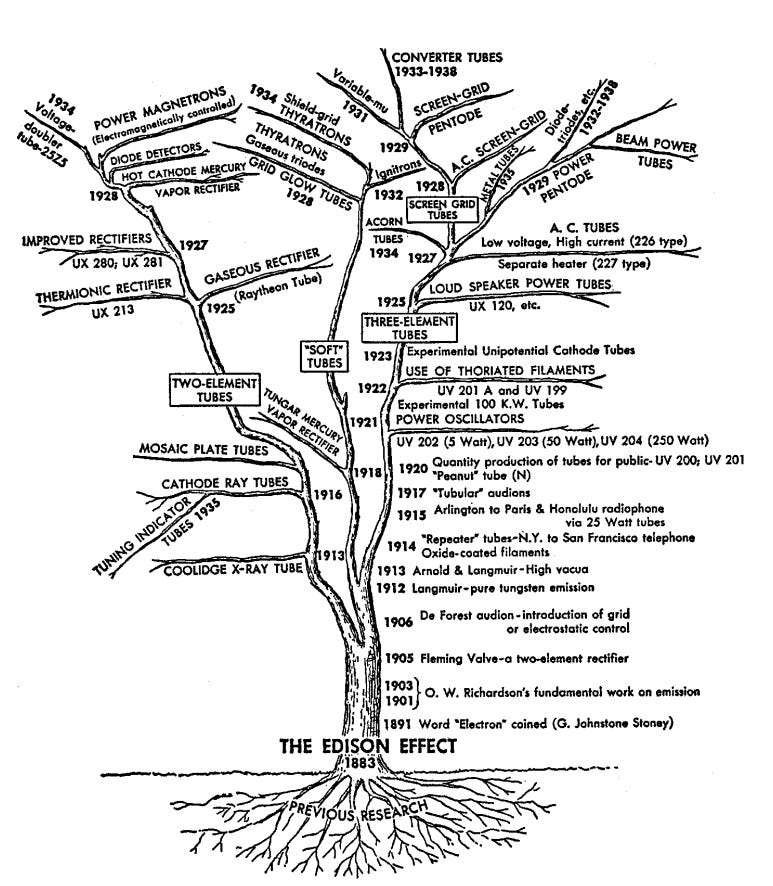

Its second axiom is that technological development follows an internal logic — a structure determined not by us, but by the underlying shape of the technology tree. The idea of a “tech tree” is itself techno-deterministic: the technologies that make up the trunk of the tree must precede its far branches. You can’t invent the smartphone without batteries, nor batteries without an understanding of chemistry, itself necessitating advances in metallurgy, glassmaking, mathematics, and more.

Examples abound. You can’t have microscopes without glass, no space travel without calculus, no nuclear power without atomic physics, no modern aviation without aluminum smelting, no industrialization without the coal-powered steam engine, and, arguably, no scientific revolution without the printing press and, later, no rapid scientific progress without industrialization itself.

We can call this acknowledgment of necessary dependencies “weak determinism”; most find it intuitive. A stronger determinism would further concede that — even when certain technologies or conditions aren’t strictly necessary for others to emerge — technological development still follows an internal logic ruled by a myriad of weak dependencies, market incentives, gains in efficiency, and the properties of technologies themselves. Strong technological determinism moves the human inventor out of the usual focus, and instead centers the broader economic, technological, scientific, and social conditions that enable technological progress.

To weigh the evidence for strong determinism, we can ask: what would history look like if we did live in a techno-determinist world?

In an October 2025 post, the AI company Mechanize offered two arguments to defend technological determinism: first, that simultaneous and independent discovery of technologies is common in history.2 Examples include the Hall–Héroult process to smelt aluminum, the jet engine, and the telephone, as well as conceptual breakthroughs, like calculus in the 1670s, evolution by natural selection in 1858, and many, many more examples not mentioned in their post. This widespread simultaneous discovery is exactly what we would expect if technological development were largely deterministic, where each discovery follows a long string of dependencies. Once the prerequisites for a discovery are in place and incentives emerge, multiple groups will converge on it independently at a similar time.3 Conversely, if discovery flowed mostly from individuals’ stroke of genius or serendipity, we should expect simultaneous discovery to be coincidental and rare.

Their second defense is that isolated societies have consistently converged upon the same basic technologies: the wheel, intensive agriculture with terracing and irrigation, similar city layouts, cotton weaving, metallurgy, writing, and more.4 If we lived in a technologically contingent world, we should expect isolated societies to independently forge (or at least stumble upon) wildly different technology trees. And instead of trade and technology transfer leading to societal convergence, we should see different societies choose divergent technological paths, whether due to randomness or intent.5

I find these two points compelling. But Mechanize’s post goes beyond arguing for the kind of strong technological determinism I defend here, into what Luke Drago terms “Technocalvinism.” As he defines it, Technocalvinism is “the idea that technological development is preordained beyond human control, leaving you blameless for your actions.” The Mechanize authors write:

Whether we like it or not, humanity will develop roughly the same technologies, in roughly the same order, in roughly the same way, regardless of what choices we make now…

Rather than being like a ship captain, humanity is more like a roaring stream flowing into a valley, following the path of least resistance. People may try to steer the stream by putting barriers in the way, banning certain technologies, aggressively pursuing others, yet these actions will only delay the inevitable, not prevent us from reaching the valley floor.

I largely agree with the techno-determinist view they lay out. We are, as a civilization, running blindly along the branches of the technology tree, feeling our way forward as we go, following the path of least resistance. To say that we’re usually actively choosing which paths of the tech tree to go down would be, in my view, naïve. Technological progress flows instead mostly from much larger, impersonal forces over which individuals exercise little control. And, when there are overwhelming incentives to develop a certain technology, there is little that can get in these forces’ way.6

And yet I disagree with the conclusion that human agency cannot meaningfully shape technological development. Even on this strongly techno-deterministic view, humans have substantial agency over technological development. Exercising this agency is one of the most important things we can do. Later in this piece, I offer a list of R&D projects that we should accelerate to prepare the world for advanced AI and invite your own pitches.

In defense of human agency

Yes, the tech tree is largely discovered, not forged. And simultaneous and independent discovery are solid evidence for determinism on long time horizons. But on shorter time horizons, our active choices to alter default outcomes can have lasting consequences.

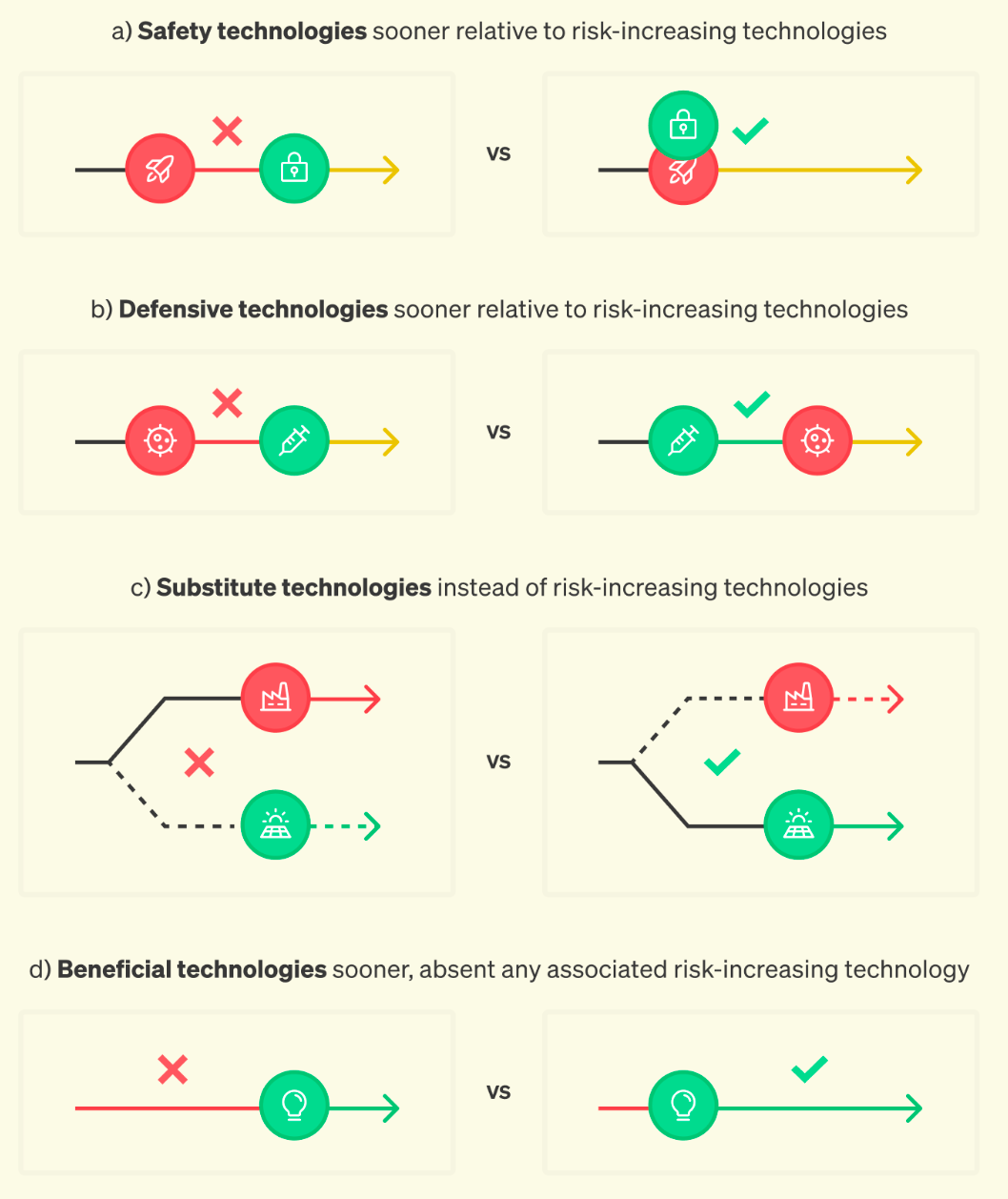

What could these choices look like? The image below illustrates a few possibilities. Positively shaping the course of technological development often means accelerating the R&D of beneficial technologies — be it because they mitigate the risks or harms of new technologies or environmental threats (a, b, and c below), or because the technology itself is immensely beneficial (d below), such as antibiotics, cancer cures, etc.

Exercising this agency makes all the difference when a game-changing technology, like nuclear weapons, is developed — especially when the technology’s impact on the world is largely mediated by how it is developed, and whether appropriate safeguards for its disruption are developed in a timely manner. Or when accelerating the development of a technology can save millions of lives (indeed, this is the reason Mechanize provides for wanting to accelerate labor automation: expediting the arrival of a world of abundance, longevity, and unprecedented wellbeing).

Earlier I asked, “what would history look like if we did live in a techno-deterministic world?” and provided what, to me, is compelling historical evidence for a strong form of techno-determinism.7 Now to the question we are actually interested in: what does history say about humanity’s ability to shape technological development?

Historical examples

1. Steering the development of a strategically decisive technology has immense effects

Nuclear proliferation has certainly been much slower than it would’ve been without active effort from the US and other governments and an expansive nonproliferation apparatus. According to a Brookings report, from 1949 to 1964, “an overwhelming majority of classified and academic studies suggested that proliferation to more countries was inevitable.” In 1960, then-Senator John F. Kennedy warned that “there are indications because of new inventions, that 10, 15, or 20 nations will have a nuclear capacity, including Red China, by the end of the Presidential office in 1964.” In those four years, only two countries — France and China — developed nuclear weapons. And only four more have developed them since. This success in limiting proliferation would not have come by default — nowadays, building a nuclear weapon is actually not that hard for even moderately-developed countries, and the military advantages of a nuclear arsenal are immense.8 Limited proliferation was the result of decades of effort by American and allied statesmen to contain the most dangerous technology ever developed.9

Limiting nuclear proliferation to nine nations is a success we can measure. Harder to appreciate are the silently averted disasters, like what might’ve happened if permissive action links (PALs) had never been developed. PALs are mechanisms used in modern nuclear weapons to prevent them from being armed or detonated without the right authorization code; without them, a terrorist could steal a nuclear weapon, or a disgruntled or insane military general could attempt a launch without proper authorization.10 Maybe we would’ve seen unauthorized launches of nuclear weapons already. Maybe these launches would’ve triggered a full-scale nuclear war. But we’ll never know, because we actively pursued R&D to create something like PALs.

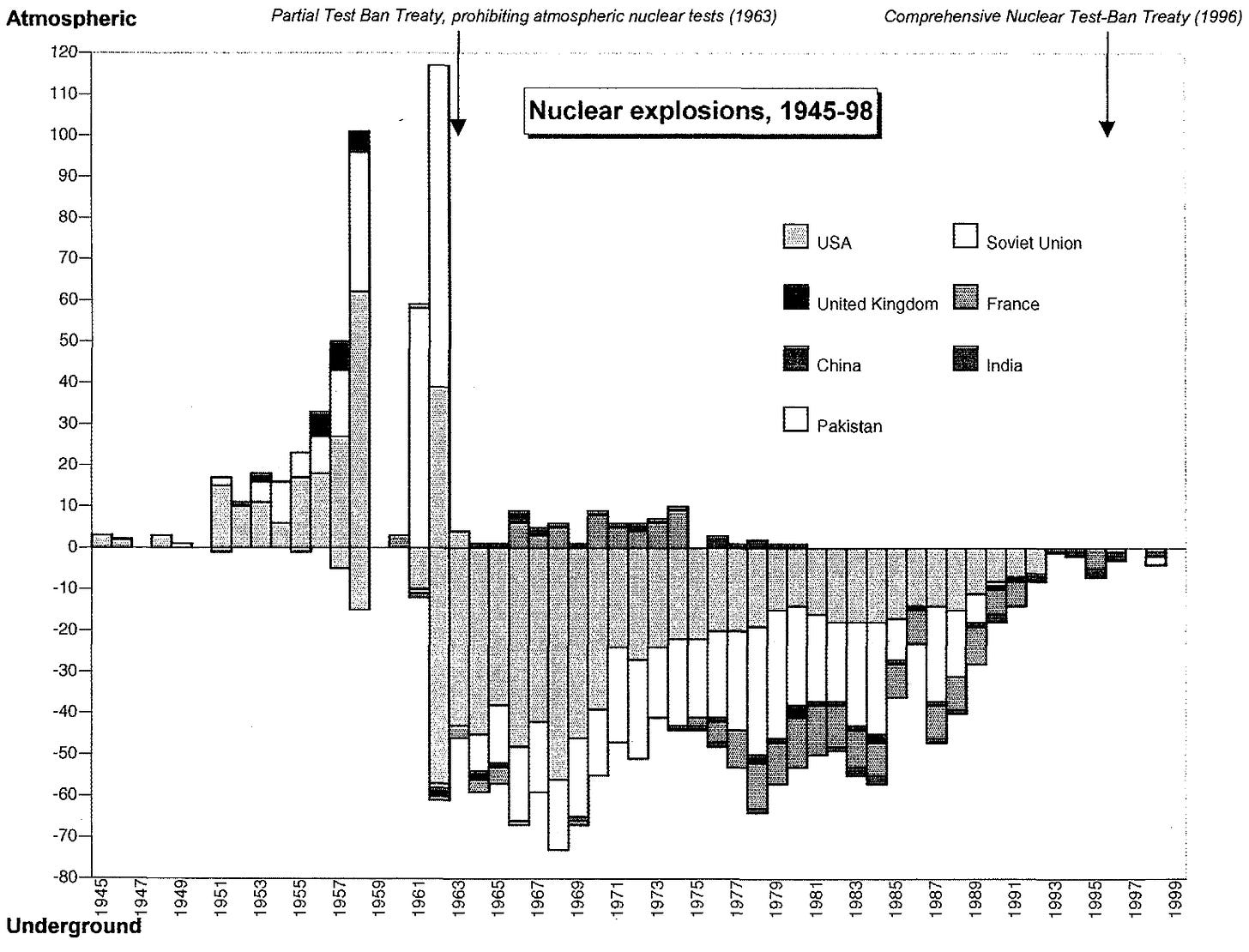

Take another example, also related to nuclear weapons.11 In 1960, the US, UK, and Soviet Union were negotiating limitations on nuclear testing. Because a state cannot be sure that its nuclear weapons work without testing them, a comprehensive and verifiable nuclear test ban is seen as an important pillar of any successful arms control negotiation. At the time of these negotiations, we lacked the technical ability to reliably detect underground nuclear tests, making a comprehensive treaty unverifiable. These limitations led to the Partial Nuclear Test Ban Treaty in 1963, which covered only detectable types of nuclear tests. Just two years later, researchers developed the Fast Fourier Transform algorithm, making it feasible to distinguish underground nuclear explosions from earthquakes with real-time seismic analysis. But the algorithm arrived late — the 1963 treaty had already excluded underground tests, so testing moved underground (see the graph below).12

It took almost three decades, an arms race that peaked at over 60,000 nuclear warheads, and over 1,300 underground tests before the Threshold Test Ban Treaty was ratified by the US and USSR in 1990.13 This illustrates two things: the importance of human agency in controlling a dangerous technological competition, and the immense costs of not having technological solutions ready before critical points are reached. Had we put as much effort into building treaty verification technology as we did into building the bomb, could we have avoided the nuclear arms race?

2. Altering the sequence in which important technologies are developed can have long-lasting effects

While the tech tree is less fixed on short time horizons, this fact wouldn’t matter much in isolation. Say you accelerate the development of one technology by two years, putting it ahead of another one. Does that just leave you where you would’ve been two years later anyway? Not always. Changing the sequence of development matters if an acute event — perhaps fueled by tech development itself — creates critical windows of vulnerability, during which an offensive technology is developed or a destabilizing situation arises, but no defensive/stabilizing counterpart has been developed yet.

For example: The claim “a COVID vaccine would’ve been developed eventually” is true, but it matters that it was developed ~10 months after the start of the pandemic, as opposed to 10–15 years later, as normal vaccine development timelines would indicate. Biotechnology companies would not have managed the fastest vaccine production in history without coordinated, intentional acceleration, in part through interventions like Operation Warp Speed. These efforts saved millions of lives.

Now for a hypothetical example. Newer scholarship suggests that nuclear weapons were likely not a defining factor in the Allied forces winning WWII in the Pacific Theater, but let’s consider a counterfactual: what if Nazi Germany had not already capitulated, and the Soviet Union had not threatened Japan with invasion?14 In that world, the Manhattan Project could’ve made the difference between a US-led world order and a fascist one.

Were nuclear weapons going to be developed at some point “anyway”? Yes, probably. But that’s not the point. The point is that the world is decisively different depending on whether a democracy or a fascist regime develops them first.

And were PALs going to be developed at some point? Yes, probably. But whether it happens soon after the development of nuclear weapons or decades later is significant. The difference may be millions of lives lost.

Technologies that arrive first also attract disproportionate follow-on R&D, compounding their lead into durable path-dependencies. This evolutionary dynamic means that the conditions under which a technology emerges can lock in for decades.

Before getting to AI — the actual motive for this piece — let me state the broad thesis I’m defending: tech trees have real, hard constraints. Beyond those constraints, almost all technological development happens in a decentralized, impersonal way, driven more by default incentives, market dynamics, soft-dependencies, and efficiency than by individual geniuses and inventors choosing the path forward. Observing from afar, it may seem like the only realistic choice is to abandon any hope of positively shaping technological development. But there are small windows of opportunity for exercising agency, in which efforts to alter the default outcomes can yield long-lasting results.

I think we are now in one of those moments in AI development, but our chance is slipping away fast.

So what do we do about AI?

The Mechanize piece makes a straightforward argument: since full automation of labor will happen anyway, best to speed it along and get the benefits of AI sooner.

I sympathize with this reasoning. As I’ve written at length elsewhere, the potential upside of AI is immense. Mechanize seems to care about bringing these benefits about as fast as possible, as do I, because the world desperately needs them.15 The world is much better off thanks to progress, but it is still awful, and it can be much better yet.16

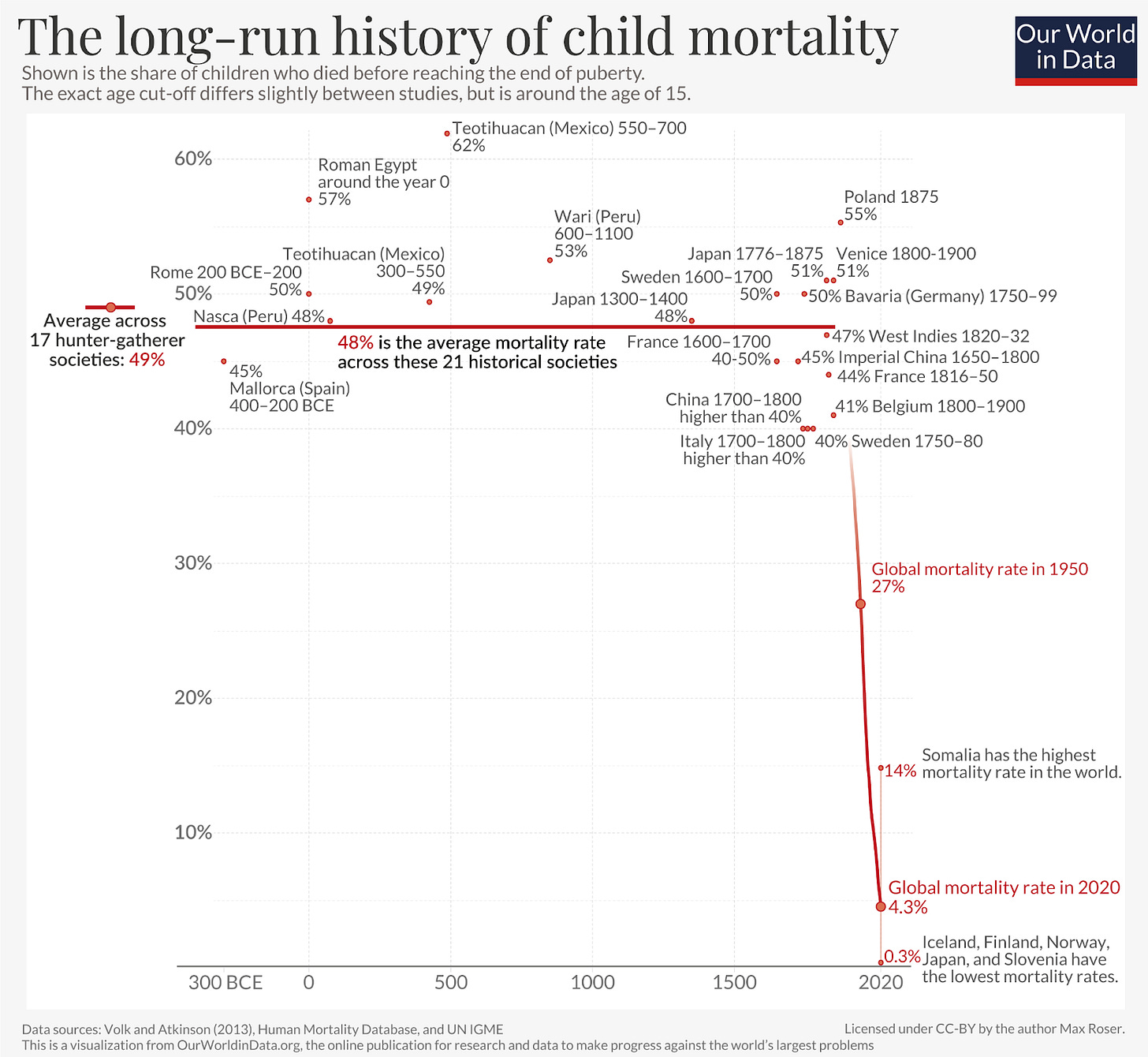

Virtually all of the large gains in human welfare have stemmed from economic growth and scientific and technological progress. If we had somehow delayed the Industrial Revolution by a century out of fear of change, that plausibly would have been the greatest mistake we’d ever made.17

It’s possible that we are on the verge of curing our deadliest, most debilitating, and dehumanizing diseases. It’s possible that our descendants will look back on the people of the early 21st century and pity us, just as we pity those who had to endure the Bubonic plague, measles, polio, tuberculosis, or who had to endure the death of a child to what today is but a minor infection.18 I hope they’ll look back and see us as the unlucky last few generations that still had to endure cancer, heart disease, obesity, depression, Alzheimer’s, and yes, even abject poverty and psychopathy.

You’ll have to forgive my perhaps naïve optimism about the future — based on our record of the recent past, I can’t help myself. The year 2025 alone produced enough medical breakthroughs and scientific advancements to inspire optimism for an entire generation.19

If delaying the march of progress in the past would’ve been a grave mistake, failing to accelerate it now would likewise prove to be so.

So if technological and scientific progress are so important, and advanced AI could accelerate it, why not just rush ahead?

One reason is that, if AI can do almost anything a human can, it will be dual-use by definition. It’ll be key for cyber-defense and cyber-offense, for vaccine or antibiotics discovery and gain-of-function pathogen research, for autonomous passenger vehicles and autonomous military drone swarms, for the discovery of miracle cures and for the creation of wonder weapons likewise beyond our comprehension.

Beyond blatant misuse, this AI had better be reliable and broadly aligned with our intent. I don’t want to live in a world where fully autonomous and unaccountable AI agents pursue their own objectives, make their own money to spend as they wish, direct thousands of other instances of AI agents toward working on their own goals, and have those objectives be in conflict with ours.

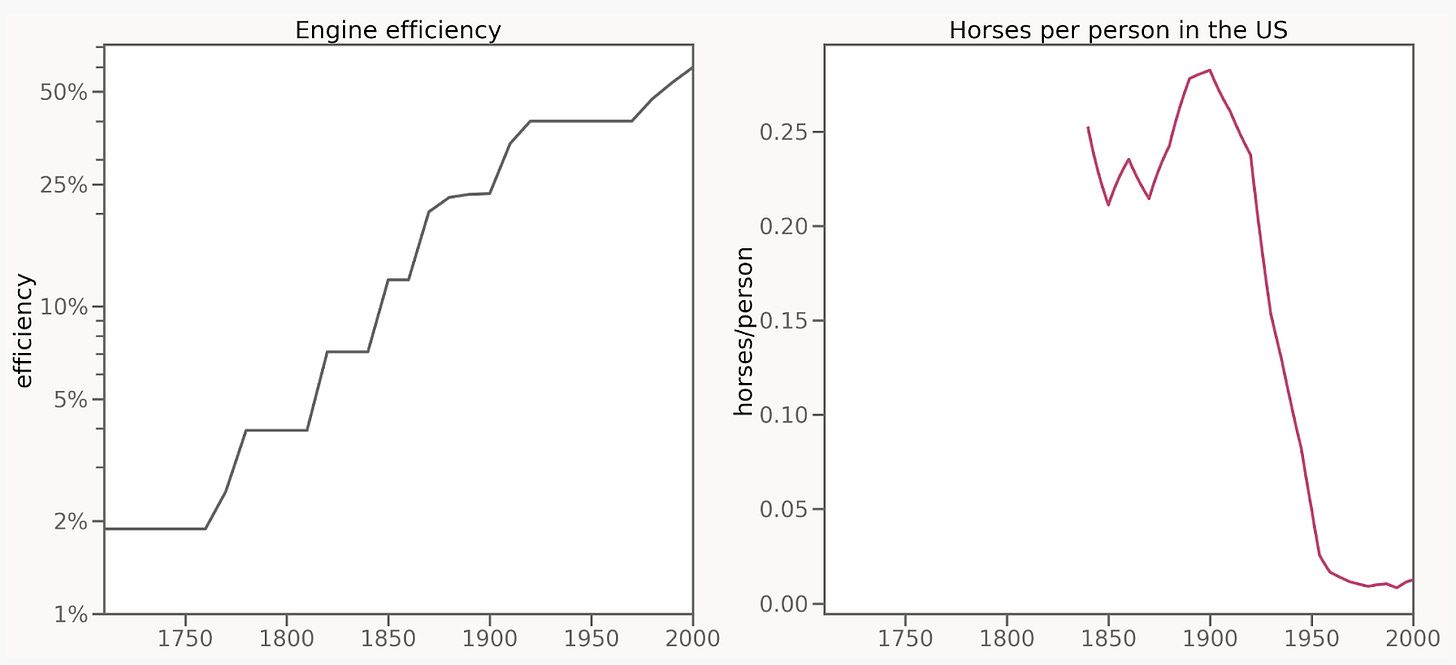

Even with aligned agents and robust protections against misuse, the broad automation of human labor could greatly decrease the power of the common man, potentially leading to extreme concentrations of power and a broad disempowerment of the population. The Black Death killing 30–50% of Europe is often credited with catalyzing the demise of serfdom in Western Europe: as the supply of labor fell, its importance grew, which allowed serfs to demand better working conditions. If AI inverts this dynamic by making labor abundant and cheaper than human wages, we might expect the opposite effect on bargaining power. Though I fully agree that automating certain parts of the economy generally leads to more and better employment elsewhere — as it has in the past — I don’t discard the possibility that future AI will be different.20 At the extreme, general-purpose AI agents and autonomous robots that (near-)perfectly substitute for human labor could make us as useless for most tasks as horses became for most transportation.21

I’m not an economist, and I won’t try and give a pronouncement here on whether AI will lead to the full automation of labor, and what that would mean for us. But economists themselves don’t seem to be sure — transformative technologies have an uncanny way of shaping the human experience well beyond their initial intent.22

Our liberal democratic institutions are a civilizational achievement that should not be taken for granted. They are as much a product of thinkers like those that led the French and American revolutions, as of the conditions of technological and economic development that enabled that thinking to become reality by empowering the general population. Just as easily as this broad empowerment can enable democracy, broad disempowerment could take it away.

Enough has been said about these risks already. The calculus is really quite simple: the development of non-human entities that can do everything a human can do with a computer is a really big deal, and it can go very well for us, or very poorly.

There is no fundamental reason why everything should go well; no law of the universe conspiring to make things better. Borrowing Peter Thiel’s taxonomy, we should be definite optimists about AI development. Instead of vaguely hoping that the technology tree and the powers that be deliver benefits while avoiding the risks, we should take charge and design a future that lives up to our optimism.

My point is that though the consequences of inventing new technologies are hard to predict, proactively mitigating the risks that new technologies create is not a lost cause. When you invent the car, you also invent the car crash. The answer shouldn’t be to throw our hands up and accept that progress requires traffic fatalities. Nor should it be to attempt to halt the creation of cars. The appropriate response is asking, “how fast can we also invent the seat belt?”

Reaching for better branches

I hope I’ve convinced you that we have real agency to shape technological development, even in a broadly techno-deterministic world. In the short run, tech trees are highly contingent and shapeable. And in fact, it is because technology is one of the strongest determinants of human welfare that steering technological progress is one of the most important things we can do.

Whether AI progress leads us to a better or a worse future could be overdetermined by the inherent qualities of the technology. Perhaps it’s in the nature of these systems that they cannot be durably aligned with human values. Perhaps it’s in our own nature that our liberal democratic societies crumble when enough people become substitutable by machines. But neither is a priori a foregone conclusion.

The destination reached could well depend on contingencies, such as whether AI systems will be interpretable and steerable before they have broadly human-level intelligence. (Will we have the PAL-equivalent ready before we get the Bomb-equivalent?) Or it may depend once more on whether a liberal democracy or a dictatorship gets the technological advantage in a critical early period. This is the level of resolution of the tech tree that matters, and it’s also the level of resolution at which actors can effect lasting change.

We are embarking on a battle for stability despite rapid progress, for a progress that actually benefits people. That “battle” will be fought everywhere. It’ll be so ubiquitous that it’ll look from afar like the great techno-determinist machine advancing at its pre-determined pace in its pre-determined direction. But it’ll be full of small wins and losses that will likely determine humanity’s ultimate course.

The ideas we already have

Over the course of 2025, colleagues and I assembled The Launch Sequence: 16 concrete projects to accelerate AI’s benefits while building safeguards against its risks.

The core premise mirrors this essay’s argument: If technology is a major determinant of human welfare, then steering its development is among the most important things we can do. Assuming advanced AI will be developed, and that its capabilities will diffuse widely, what should we build to prepare?23

Some proposals target the “seat belt” problem directly — building defenses before vulnerabilities arise:

Operation Patchlight and The Great Refactor would use AI to proactively harden our cyber infrastructure before AI-powered cyberattacks undermine it at scale.

Hardware-Based Verification would enable faster AI diffusion while preventing misuse, and eventually serve as the basis for lightweight domestic policy or effective international treaties.

Preventing AI Sleeper Agents would red-team American AI systems against adversarial tampering — the PALs-analogue for a technology that will soon be embedded everywhere.

Scaling Pathogen Detection would build the biosurveillance infrastructure to catch the next pandemic early — the kind of system that could have saved countless lives in 2020.

Other proposals would accelerate the beneficial applications we desperately need:

A Million-Peptide Database would generate the training data needed for AI to discover new antibiotics before resistance claims more lives than cancer.

The Replication Engine would use AI agents to automatically verify scientific findings at publication, addressing the replication crisis that wastes billions in research dollars annually.

Self-Driving Labs would build robotic systems to test AI-generated material discoveries, closing the gap between digital prediction and real-world validation.

The ideas we’re looking for

If you’ve read this far, you likely have ideas of your own. We’ve reopened The Launch Sequence with a rolling request for proposals (RFP). We’re looking for concrete, ambitious projects to prepare the world for advanced AI — whether by accelerating critical safeguards, unlocking scientific and medical breakthroughs, or building the infrastructure for more resilient institutions.

The first stage is just to submit a short pitch (200–400 words). If your idea is promising, we’ll work with you to develop it further and connect you with funders ready to act. Authors will receive a $10,000 honorarium, and other bounties are available. This project is advised by George Church, Matt Clifford, Kathleen Fisher, Tom Kalil, and Wojciech Zaremba.

We have much to do and no time to waste. Do not surrender to the default tech tree — there is no guarantee that it will be merciful. If we are to reach better futures, we must build them ourselves.

Read the RFP and submit your pitch here → ifp.org/rfp-launch

Acknowledgements: I thank Luke Drago, Gaurav Sett, Adam Kuzee, and Jonah Weinbaum for useful feedback. All errors are mine.

And any differences between them are largely determined by their environment: the climate, the domesticable animals that happen to live there, proximity to a shore, etc.

Mechanize seeks to help automate white-collar work as fast as possible to expedite the benefits of AI — something which they claim cannot be done effectively by just accelerating medical AI or other narrow applications. Mechanize’s post isn’t the first to defend technological determinism, of course. But it is useful for my purposes because of its focus on AI and labor automation. This piece isn’t so much a response to them as it is me borrowing their arguments as a useful comparison.

In a 2025 Construction Physics piece “How Common is Multiple Invention?” Brian Potter writes, “I was still surprised that over 50% of inventions in the time period looked at had some type of multiple effort to create, and that nearly 40% weren’t simply someone having the idea or working on the problem, but successes or near-successes. I was also surprised that this ratio didn’t vary much across time and across categories of invention.”

I will not dwell on this point at length, and recommend that you read their post instead.

At the extreme, in a fully technologically nondeterministic world, we’d expect to see societies that reached the Steel Age but never used copper, bronze, or iron, or Iron Age societies that never tamed fire. But we don’t. There are certainly many examples of societies that skipped parts of the technology tree because of direct technology transfer from more technologically advanced societies. But once superior technologies become available, be it through initial discovery or trade, they are largely adopted.

This is especially true of technologies that offer decisive economic or military advantages to those who develop them — the rates of multiple independent discovery are higher in the dataset of “historically significant inventions” analyzed by Brian Potter above than in innovation in general. The greater the incentives to solve a problem, the more researchers and investors will work on a solution, and the higher the likelihood that the solution will be unlocked independently multiple times once the right precursor technologies are in place.

This is far from a complete defense of technological determinism. My goal is merely to present a version that rings true to me. An earlier version of this piece was titled “My Techno Determinism” — a riff on Vitalik Buterin’s excellent post, “My techno optimism,” which is an inspiration for much of my work.

Nuclear weapons are, after all, 1940s technology, and the fundamental physics insights have been public knowledge for decades. Evidence for this is the “Nth Country Experiment,” a 1964 Lawrence Livermore experiment where three physics PhDs with no weapons experience were hired to design a nuclear weapon using only public information. They produced a “credible” implosion weapon design in less than three years. (And they focused on the harder implosion design, as opposed to the gun-type design, because they deemed the gun-type design to be so easy to build it did not need to be tested.)

I copied part of this paragraph from a footnote in Preparing for Launch.

For a more thorough explanation and references on PALs, see Steven M. Bellovin, Permissive Action Links.

I borrow many examples from the development of nuclear weapons both because I am familiar with it, having written my thesis on AI-nuclear integration, and because it is an illustrative example of how human agency can have profound effects on technological development and its consequences. I don’t mean to draw an analogy between nuclear weapons and AI — in fact, I believe the analogy is largely overstated.

This paragraph draws heavily from the introduction of “Secure, Governable Chips” (p. 5) by the Center for a New American Security.

This treaty prohibited “large” nuclear tests, i.e., those exceeding 150 kilotons. The Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty was then signed in 1996.

Whether the nuclear bomb was a crucial factor leading to Japan’s surrender is a contentious topic that I won’t get into here. You can read this summary of the debate from the Atomic Heritage Foundation, which lists various views on the matter and concludes that “with the shakiness of the evidence available, it is impossible to say for certain what caused the Japanese surrender... It seems like there is no easy answer to the questions surrounding surrender, and historians will continue to debate the issue.” For a traditionalist interpretation that the bomb was the only decisive way to end the war quickly without an invasion, see Richar Frank’s “Downfall” or its review by Frederick Dickinson.

Of course, Mechanize is a for-profit company that would stand to profit from being the ones to capture part of the value of an economy that they helped automate.

Paraphrasing Our World in Data, “The world is awful. The world is much better. The world can be much better.”

I’ve made this claim to people in the past, and they sometimes disagree with me because the Industrial Revolution’s pace and timing may have culminated in the brutal fascist and communist regimes of the 20th Century. In this case, it’s hard to know the counterfactual. If the Industrial Revolution started 100 years later, or if it proceeded more slowly, would we have had a smoother ride? It’s not clear to me. All that time, who consoles the mothers of the roughly half of all children who would die before adulthood? Who consoles the roughly 80% of people so poor they were unable to meet their basic needs? Even if it were true, I think this rebuttal shows that people concentrate on the identifiable costs of progress, rather than on its oft-diffuse but larger benefits.

Some may understandably feel pessimistic about the current state of science in the US. I share these concerns. The rapid progress we’ve enjoyed until now should not be taken for granted.

For more on automation leading to more employment elsewhere, see David H. Autor, 2015, Why Are There Still So Many Jobs?, Journal of Economic Perspectives.

There’s much debate about whether a general-enough AI would be a perfect substitute for human labor, which I can’t fully do justice to here. Maxwell Tabarrok wrote a thoughtful rebuttal of the case that yesterday’s horses are tomorrow’s humans, which does not fully reassure me. I think it obviates the case where AI inference is so abundant it is virtually unlimited when compared with human labor supply, and so cheap that it’s not even worth employing humans in tasks where they have a comparative advantage. It also presumes that humans will own AIs, but I think this doesn’t necessarily hold for AI systems that are advanced and agentic enough. It also doesn’t preclude the possibility that humans may indeed turn out to still be relevant for certain tasks, but that those will be undesirable ones; for example, if abstract reasoning and computer use are much easier to automate than physical manipulation, humans may only be employable as physical laborers following the instructions of AI managers.

No one purposefully kicked off the Agricultural Revolution, expecting it to break with hundreds of thousands of years of a hunter-gatherer existence, leading to the creation of permanent settlements and thus population explosions, specialization, and the steady buildup of culture and knowledge. Gutenberg could hardly have imagined that his printing press would lead to or enable the Renaissance, Reformation, and the Scientific Revolution. And though far more predictable, I also don’t expect the Wright brothers to have anticipated fire-bombings of population centers as they precariously experimented with their early contraptions.

We defend this position more directly in the foreword to the collection, Preparing for Launch.

This is a great piece, thanks for writing it up. I've been writing out some similar ideas in parallel, also spurred on by the Mechanize essay.*

I really like the Fast Fourier Transform algorithm example, that was new to me. I also overall agree that there is a greater amount of agency to be exerted, due to the fact that as technological development accelerates and more changes are compressed in a smaller number of years, then even seemingly minor delays or speed-ups (of 'just' a few years in either directions) can start exerting very significant effects on welfare or overall trajectory safety.

Still, I think even the account here, while directionally correct, still overstates the degree of determinism in historical tech development, and understates the contingency (though granted technological contingency does not necessarily equate to easy technological choice). This is not a conclusion I initially expected to reach since I'm quite tech determinist by disposition myself. But some points that contribute to this are:

- I think you (still) overstate the case for technological convergence across premodern societies, as I'll show with a review of around 90 counterexamples.

-in particular, re. 'societies that have been cut off from technological progress...have ways of life similar to those of every other technologically primitive society around the world, be it contemporary or ancient' -- It was generally my understanding that contemporary primitive societies are not considered to provide a representative guide to the state of other societies in ancient times.

- One important nuance to tech tree-like arguments is that--crucially, unlike actual trees, and unlike evolutionary family trees or the tree of organic life, the 'tree' of cultural and technological artefacts allows (and in fact often depends) on branches not just branching outwards but fusing and recombining with one another (cf. the 'innovation as recombination' perspective in https://mattsclancy.substack.com/p/innovation-as-combination and https://www.newthingsunderthesun.com/pub/3wpc3plu#the-landscape-of-technological-possibility ]. Importantly, given the degree and extent to which even supposedly revolutionary technologies often depended on the recombination of existing elements (see Basalla, The Evolution of Technology, https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/evolution-of-technology/72D7695EE9A2BAFB75EFE648D4222A03 ), this suggests that the 'narrowing' and tech sequencing constraints of the tech tree will only really bite at a low level of technological invention (i.e. when you're close to the trunk, and there are only very few branches that might recombine). In other words, if you are the Neo-Assyrian Empire, you can't hope to create rifles without first mastering metallurgy. But precisely when you are a modern state, you have a far larger bucket and menu of existing branches to rework and apply to solving a particular problem. And so you can come up with very different technological solutions and doctrines (e.g. you can achieve forms of 'solar power' both by running a tech tree through semiconductors ->photovoltaic cells->solar cells.... or by running it through wind turbines + solid lightweight construction materials = solar updraft tower https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Solar_updraft_tower . To be sure, they aren't equivalent in their performance envelopes (SUTs are much more land-intensive). Neither do they necessarily offer the same payoff gradient across the tech tray, but there's still a case in point of how tech-tree like arguments should in fact lean towards *greater freedom* the further along you get.

- I think a few challenge with Bryan Potter's otherwis interesting analysis is that it doesn't imho sufficiently account for how at least some apparent cases of simultaneous invention (eg lightbulbs) seem like they're much better described as serendipitous final simultaneous success by teams working independently, but at the head of sustained effort for many years by many inventors towards a publicly known goalpost. That does not mean that the original path was predetermined, just that, once the goalpost was established, many inventors would be incentivized to pursue it. So this at best applies to things and ideas that are known in advance to be huge, and that still leaves out a very important class of technologies that are only known ex post to be useful [although I'll grant that A[G]I is currently perceived as such a shared goal]

- Any argument that depends on simultaneous independent invention, should also reckon with the exact inverse phenomenon of collectively unusually delayed inventions (or ideas), which came far past the time by which the technological pre-requisites seemed to obtain (e.g. balloons, barbed wire, and another 20 or so cases I'll survey)

- you're arguably still understating the track record of (horizontal) nuclear restraint: as I discuss in my recent book**:

> Based on IAEA databases, there have historically been 74 states that decided to build or use nuclear reactors. Of these, 69 have at some time been considered potentially able to pursue nuclear weapons. Of these, 10 states went nuclear, 7 ran but abandoned a nuclear weapons programme, and for 14–23 [other] states evidence exists of a considered decision not to use their infrastructure to pursue nuclear weapons.

Importantly, many of the cases of abandonment of development actually shows that nuclear weapons are far from usually perceived as an 'irreplaceable' technology. E.g. Nasser abandoned Egypt's nuclear program and joined the nonproliferation regime, solely because he calculated he could embarrass Israel that way ( https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10736700601071637 ); in 1965, Sweden came within six months of a working bomb https://teknikhistoria.nyteknik.se/langlasning/den-svenska-atombomben/144778 before autonomously deciding to abandon the project; India fought a war with China in 1962; yet when China went nuclear in 1964, India did not initiate a crash nuclear program; rather, it just kicked the program into committees, and put it on a backburner, with an aim to eventually, slowly develop a nuclear *breakout capability*. The final decision by Indira Gandhi to go nuclear likely had more to do with a desire to distract from domestic labour union strikes ( https://www.jstor.org/stable/2539273 )... etc.

- 'If we had somehow delayed the Industrial Revolution by a century out of fear of change, that plausibly would have been the greatest mistake we’d ever made.' -- while I share your general intuition here, I do think there are a few important differences here in the sense that (i) I don't think anyone is talking about delaying AI (or, full automation) by an entire century, and (ii) it is not implausible to me that the Industrial Revolution took a lot of the initial low-hanging fruit in terms of childhood mortality, measles, polio, etc., and that, large though the costs of cancer, heart disease, obesity, etc. are, solving them by themselves would not add equivalently many QALY per person as that initial jump did, and so the upside is just a little bit more capped. (The counter case here, of course, is if you start to assume extremely transformative consequences from AI in terms of either life extension or something-something uploading). That doesn't mean that it's therefore acceptable or fine or costless to accept modest delays on full automation; but my point is simply: we're clearly just bargaining over the 'price' in this case, and there is, presumably, a break-even point on the 'cost-benefits of moderate delay' function, where that strategy is not just unreasonable, but the obvious better option. I'm not strongly wedded to this argument, but I do think it is a relevant nuance.

- As an aside; generally, there is a whole family of claims that have been called technological determinism (see Dafoe at https://www.jstor.org/stable/43671266 ), and of these, I tend to only find Dafoe's socio-technical selectionism very plausible. That tends to work only on longer timeframes and/or in very competitive environments where there's also a lot of strategic clarity over what is the usefulness of different technological steps. And so I think it supports a much weaker form of pressure or convergence (at least than entertained by Mechanize).

Anyway, some assorted thoughts, that I'll hopefully get to write about in detail more as well. For now -- thanks for writing this up, and I hope you get a ton of submissions for our Launch Sequence!

--

* see the list of questions in https://criticalmaas.substack.com/i/186864865/open-questions-about-the-past-of-technology-and-the-future-of-ai - I'll hopefully get to work some of this out more in the coming months.

** https://academic.oup.com/book/61416/chapter/533870075