Antitrust in the Marketplace of Ideas

Science is a dynamic system. Ideas come and go. Scientific and technological institutions rise and fall. Fields of research collaborate, compete, and collaborate again. Knowledge production and its various supply chains are never a stable enterprise.

This dynamism means that the output of the economy of science fluctuates unevenly over time. Certain fields may become wildly generative, producing knowledge and advances that dramatically reshape our understanding of the world and what we can do in it. Other periods can be stagnant, with fields entering long periods of incremental or nearly non-existent progress. Much like the early political economists of the 18th and 19th century that tried to understand national wealth, metascience is grasping at a common understanding of the underlying determinants of scientific wealth.

Some of my favorite papers in metascience highlight the importance of one potential determinant: the role that stardom can play in producing rigid intellectual paradigms and social networks that ossify a field and limit its ability to progress over the long run.

“Does Science Advance One Funeral at a Time?” (2019) suggests a field’s eminent participants can cause harm by enforcing orthodoxies and limiting outside contributions that can drive progress. By taking a look at the premature death of stars across biomedical research, the researchers conclude that outsiders are deterred from productively challenging these leaders while they remain alive and active in a field.

“Aging Scientists and Slowed Advance” (2022) takes a related look at aging cohorts of star researchers and shows how aging produces fields “less likely to disrupt the state of science and more likely to criticize emerging work.” Prominent scholars produce major breakthroughs early in their career, only to settle into a defensive posture later in life that discourages new upstarts. The paper suggests that this pattern repeats across many fields.

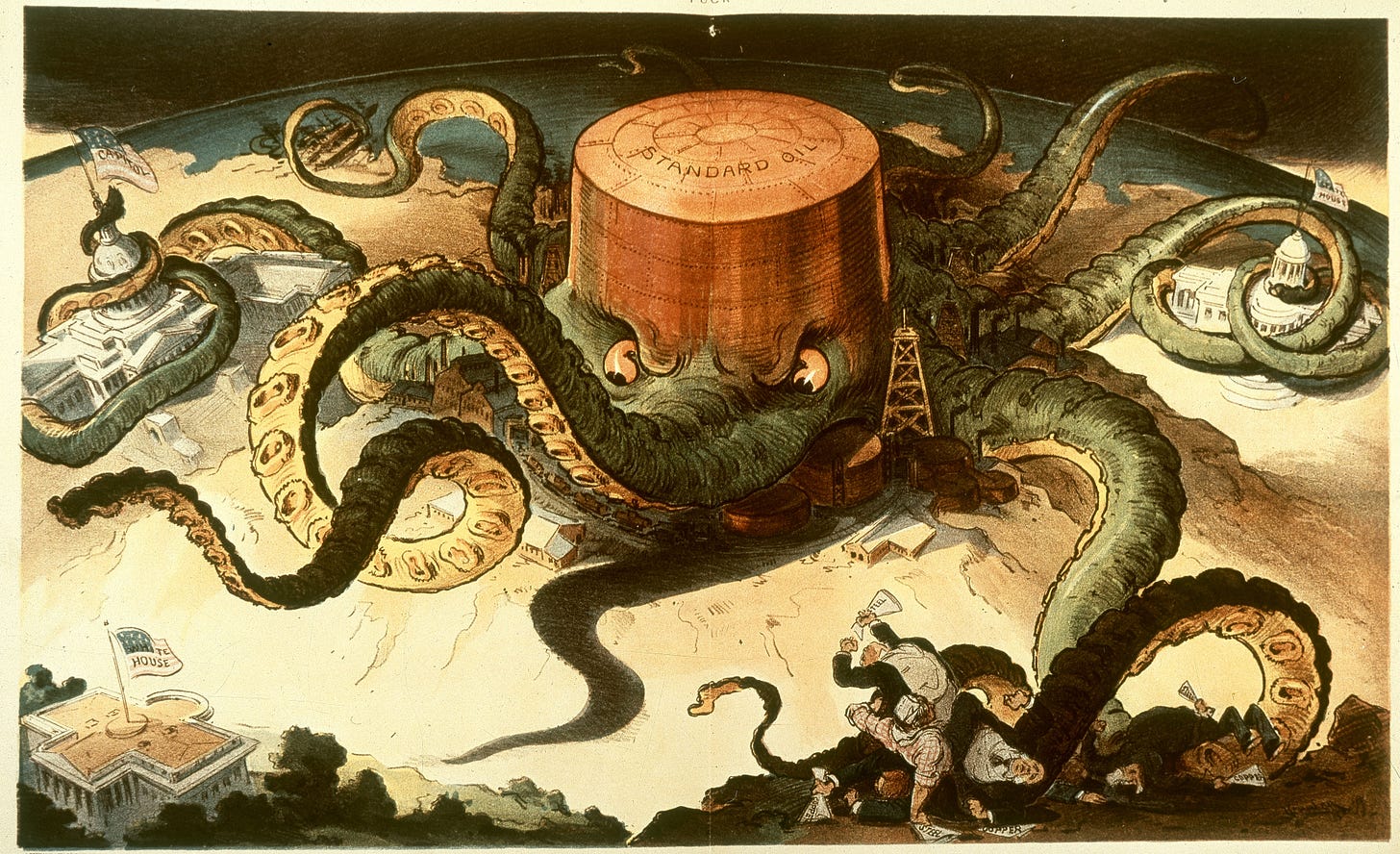

These results suggest a provocative set of related policy questions. Should science policy shoulder the responsibility of ensuring the dynamism of scientific fields? And, if so, should it proactively attempt to break the ossified intellectual monopolies that can form within fields and threaten the rate of progress?

Obviously, the government cannot literally accelerate science “one funeral at a time.” But one might imagine a set of policies that could help check the power of established scientific stars in an effort to drive dynamism in a field.

Science funders might create an “Offset Fund” that supports outsiders challenging established leaders in the field. This fund could grow in dollar terms as the number of citations received by an index of leaders grows or as time since the last major disruptive paper in a field elapses. Governments might also gradually allocate greater funds, partnerships, and key resources like data to newer institutions as a field matures, counterbalancing the advantages that established, incumbent research institutions build over time.

“Aging Scientists'' also suggests that researchers that switch into new fields exhibit positive behaviors that resemble younger scholars. We could establish grants that systematically incentivize more established, senior researchers to leave their current field for new ones, a scaled-up version of the Simons Foundation Pivot Fellowship. This might have salutary effects in opening up space for new blood in the fields these leaders depart, and create new challengers in the fields they enter.

This strategy could manifest in more dramatic ways. An Offset Fund might be set to balloon rapidly under certain “market crisis” conditions, such as severe inequality in the overall allocation of citations or research funding across a field. Similarly, a funder might deliberately encourage schism under a clear set of stated conditions, supporting the independence of upstart researcher communities desiring to start their own fields or subfields. The threat of flooding the marketplace with heterodox challengers might be sufficient to encourage incumbent star researchers to permit more intellectual competition within their domain than they would have otherwise.

One intuition driving Macroscience is that metascience will produce two related revolutions in science policy. For one, it will create the grounds for fashioning potent new levers in shaping the direction of progress. Rather than simply tinkering with the incentives to work on certain target problems and technologies, we might aim to influence deeper dynamics like the overall portfolio of scientific institutions operating in an area, or the time horizons that researchers apply to their work. The capacity to influence the level of intellectual cohesion or fragmentation would seem to be another valuable addition to the toolkit of science policy.

Second, the existence of such levers will provoke a set of macroscientific debates about the application of state power. It is impossible to avoid a set of thorny, normative questions about the role that the government should play with regards to the economy of science, and the conditions under which it should choose to intervene with its tools.

For me, the huge importance of science and technology to national prosperity necessitates a role of active stewardship by the government to protect dynamism. Like the market itself, the literature of metascience suggests that the powerful engine of research can become subject to certain systemic vulnerabilities. Relying on a field’s internal self-regulation in these cases is not a remedy. Where phenomena like intellectual monopoly within a field threatens progress, the regulators of science have a responsibility to act to restore competition in the marketplace of ideas.

Thanks to Santi Ruiz and Caleb Watney for their comments and feedback on this post.

Excellent piece. I particularly like your idea for grants that systematically incentivize more established, senior researchers to leave their current field for new ones. I proposed a more modest version of this idea in a column I wrote a few years ago. https://genomebiology.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/gb-2006-7-2-103

I like your bolder concept better.