Bottlenecks

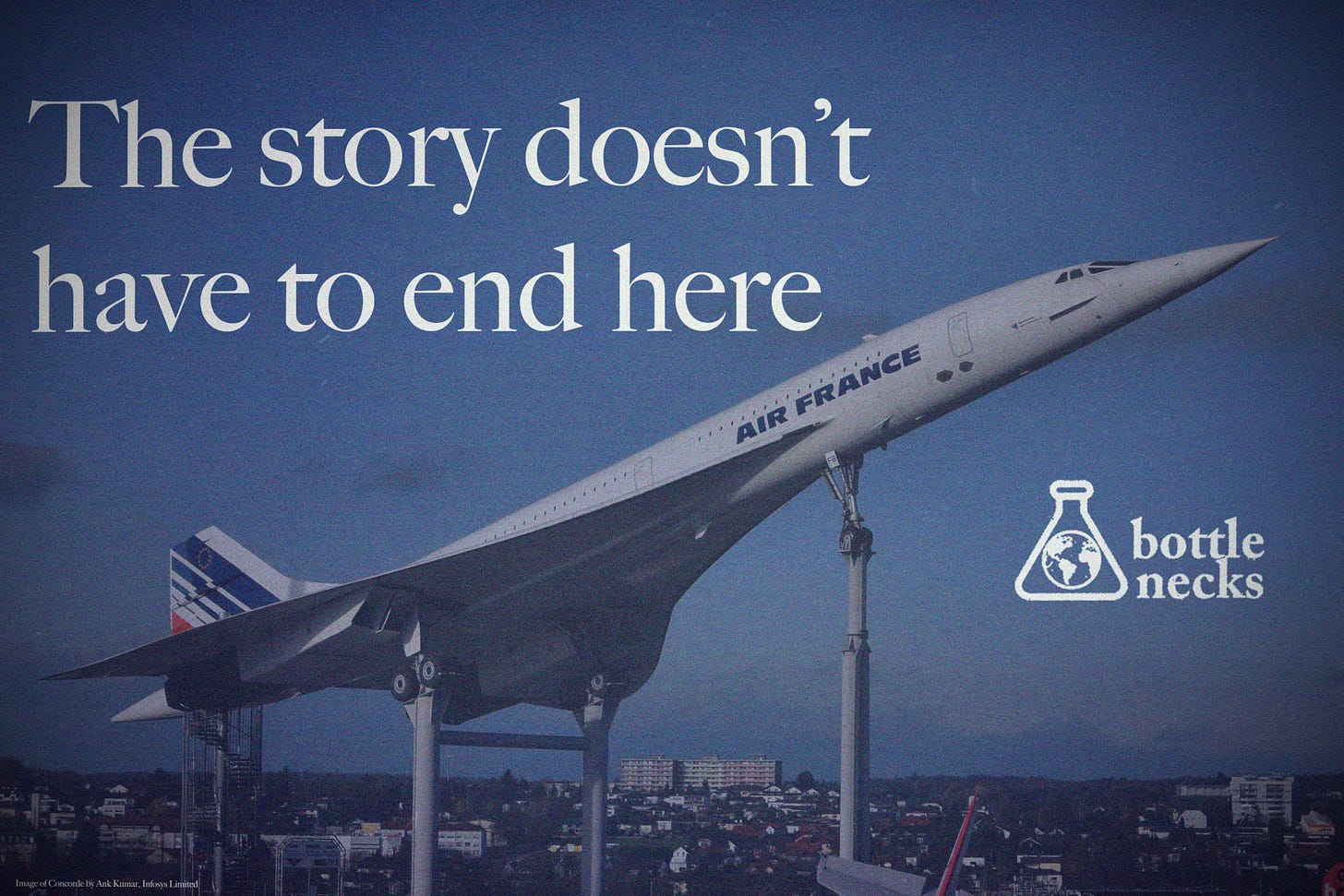

As part of my work at IFP, I’m helping to co-organize the Bottlenecks Summit, which will take place in September in collaboration with the Abundance Institute and the Foundation for American Innovation. The summit will be focused on bringing together a wide set of “thinkers, builders, creators and policy entrepreneurs working to overcome bottlenecks to human progress and abundance.”

The obvious question for an event like this is, “What bottlenecks?” The number of plausible bottlenecks to human progress is vast, and the loosely organized coalition of groups that run variously under the banners of progress/metascience/abundance will be more effective if they concentrate their efforts.

There are the familiar blockers — the problems of reproducibility, the gaps in scientific funding, the problems of permitting — but an event like the Bottlenecks Summit offers a chance to refresh the agenda and potentially set people’s sights on a new set of high-impact targets.

The excellent Kumar Garg has called for “a crowdsourced list of bottlenecks,” and it seems like the right idea. To kick off the conversation, here are some of the bottlenecks I feel have been overlooked or left on the backburner, and deserve greater sunlight at the summit and elsewhere:

Energy as the Ultimate Bottleneck. We will need more energy to push the most promising technologies that we have forward. The progress community has tackled aspects of this problem, from attacking the permitting processes that slow power construction to pushing for investments in potentially game-changing areas like fusion. But I haven’t yet seen an analysis that coheres into a comprehensive agenda to unblock the many bottlenecks that exist in the energy supply chain. The summit might serve as a good opportunity to bring the various people working on aspects of this problem together to construct this strategy and identify overlooked areas.

How I Learned To Stop Worrying and Love Team Science. The growth of team science has been a cause for a lot of hand-wringing about its effects on the initiative and speed of individual researchers. However, one alternative point of view is that team science is the present reality of research, and that unblocking it as a bottleneck is less about rejecting team science entirely and more about making it work much, much better. I’d love a discussion that wholeheartedly leans into the promise of team science and makes the bull case for making teams even bigger. Could science be done in even larger teams, much larger than the kinds of teams that we have now? What would an effective research team ten times larger than the largest research team we have now look like? How would we achieve it?

Growing the Progress Coalition. If the progress coalition is itself an important asset in unblocking inhibitors to progress, then limits on its ability to grow and execute are themselves bottlenecks. Who are the most important allies for progress as the movement grows? Could progress become a mainstream view, and does it need to? What movement infrastructure needs to be put in place to ensure that the various elements of the coalition can coordinate effectively? I think it’d be fun and productive to talk practically about how the various elements of this space work with one another, and what capacities are still missing within the broader community.

Making the Alternative Research Ecosystem Sustainable. Among the successes of the progress community has been the launch of multiple new experiments in the way that research could work: FROs, alternative publishing outlets, and experiments in research funding. How can these projects begin to move from the realm of pilots and experiments into something more resembling a permanent network of institutions and researchers? How will funding sources, talent pipelines, and research agendas need to be arranged to ensure long-run sustainability? Failing to answer these questions might leave these experiments in a continual state of precarity and marginalization, inhibiting us from capturing the benefits that truly building out a robust alternative research ecosystem might achieve.

Shaping the Rich. Philanthropic decision-making remains one of the biggest bottlenecks to progress since it shapes the movement of a huge amount of discretionary capital through society. As Matt Clancy discussed on the latest Macroscience podcast, this is partly due to structural issues that prevent funders and program managers from improving over time. What are radical steps that might be taken to significantly improve the quality of philanthropic decision-making and organizational structure? What philanthropic wealth is still “on the shelf” that might find a natural alliance with what the progress coalition is pursuing?

Got some other ones? Drop any thoughts in the comments and we’ll get a list going.

The academic promotion process has become a bottleneck. It rewards quantity, not quality. Among other things this overwhelms the reviewing system, further de-emphasizing genuine insights and contributions. Junior faculty get promoted based on churning out numerous publications.

* Agriculture -- Where did startups for farming robots go? How can robots be used to free up time for farmers to begin conserving land or rewilding?

* Housing -- Putting aside permitting reform (which would include building codes and abolishing parking minimums), how can progress studies be applied to Montgomery County, MD-style competitive, proactive public housing development? What are the main bottlenecks in modular housing supply chains, as a way of tackling construction costs?

* STEM Journalism -- Transparency and science ethics require a vibrant media, but there are workforce recruitment issues especially among local news, which the Peace Corps-style Report for America tries to solve. How can the model be leveraged to spark passion earlier in prospective science journalists, or many others?

* Creator Economy -- Similarly, the creator economy, along with the open source community in general, face institutionally-imposed bottlenecks, an example in America’s case being due to the entrenchment of the Copyright Office in the Library of Congress. How can copyleft be promoted further to improve innovation?