A Census for Science

The potential of metascience rests on its promise to offer an unparalleled account of the determinants of scientific and technological progress. Whereas earlier efforts to understand progress have relied by necessity on historical anecdote and speculation, metascience seeks to put an understanding of these complex processes on firm empirical grounding.

By necessity, this research agenda has meant that metascience has been bounded by the data available to it. As a scrappy, emerging research field, metascience has relied largely to date on the data that is accessible. This has meant leveraging information on patents, citations, and grants. Observational studies have been the default, with experimental data a relatively uncommon (but growing!) exception.

It is a truth generally acknowledged that this state of affairs means our understanding of science has gaping holes in it. As Matt Clancy has argued, this is perhaps not as bad as it might initially seem. Existing data sources indeed provide a great deal of signal on questions around innovation. But we think that one would be hard-pressed to argue that the current situation is truly ideal.

Consider that the metascience community lacks efforts to collect good longitudinal data about researcher views, norms, and preferences. The much-touted Collison-Nielsen survey from 2018 started a critical public conversation on declining scientific efficiency. What else could we learn if that survey was expanded and conducted on an ongoing basis? Scientists will often scoff at traditional metrics like citations or patents because, in their view, good science is a “know-it-when-you-see-it” phenomenon and fundamentally about good taste. Large-scale surveys of scientists could help bridge this gap by aggregating the opinions of scientists about promising (or unpromising) developments in their field and in adjacent fields.

We also lack data about the internal dynamics and culture of research organizations. How do labs organize themselves? How are budgets and resources allocated? How is time spent across roles? How are conflicts resolved? Our colleagues have launched, with support from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, a promising pilot program with the World Management Survey to try and shed light on some of these questions within biomedical labs, but traditionally they have been a black box.

We also lack good data about what is happening within private laboratories. In a world where the most pivotal work in key technologies like artificial intelligence is happening within companies, the inability to observe these processes is a major limit on understanding.

Gaps like these place fundamental limits on metascience’s ability to provide a complete account of scientific discovery and development. We have only a low-resolution picture of how researcher perceptions are evolving over time, how research organizations are structured, and how private companies are pursuing scientific discovery.

We should not be surprised that we face these gaps. After all, metascience is subject to the same perverse incentives that plague other research fields to collect, clean, and maintain valuable data. Researchers are rewarded for publishing novel results, not novel datasets. Data acquisition can be costly and labor-intensive, outpacing available research budgets. Risk-averse agencies and organizations can be slow to collaborate with researchers to launch experiments testing novel policies.

All these factors contribute to a scarcity of data that imposes major frictions on metascience’s advancement. On one hand, this could be a problem for metascience, whose backers will need to have the patience to see this effort through without strong near-term wins. But it is also a problem for policymakers, who will lack the crucial insights and policy options needed to accelerate innovation in a period of declining scientific productivity and increasing global competition.

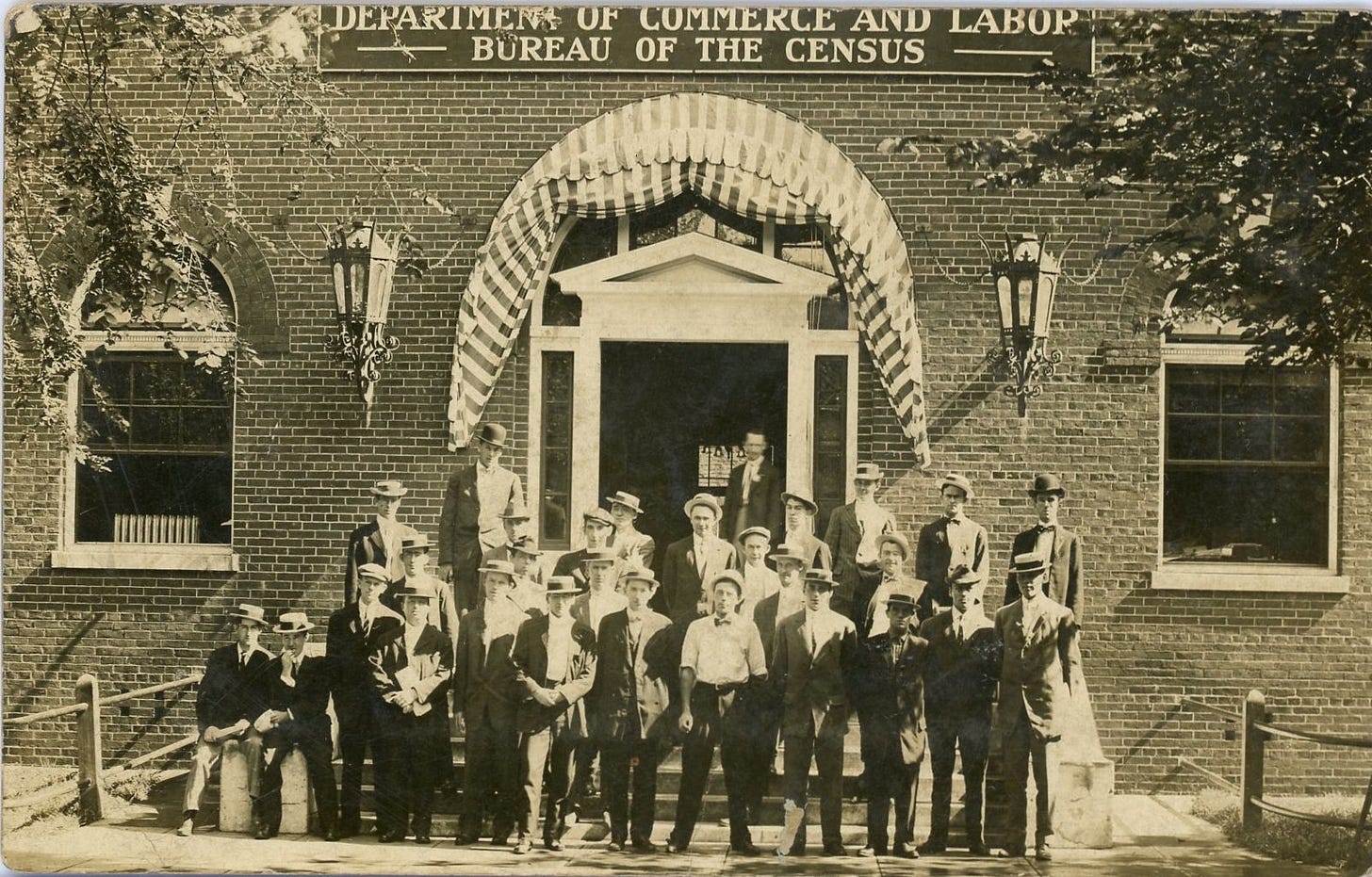

Data scarcity is a policy choice. Rather than relying passively on the data that exists, the metascience community should be seeking to proactively generate the data that give it the best chance of answering the hardest questions. What could be catalytic is an institution dedicated to closing these gaps and curating metascientific data as a public good: a kind of Census Bureau for science.

A US Science Bureau would be tasked with periodically conducting a census that would aim to provide the richest possible snapshot of the activity of the American scientific ecosystem. This effort would reach across and within fields, surveying researchers at every level of seniority, compiling data on budgets and spending, assembling longitudinal data on various metrics of research productivity, and piloting the creation of new metrics entirely.

Beyond this, the USSB might take on targeted data collection efforts. Establishing data sharing partnerships and experimental collaborations with research organizations both public and private is time-consuming. Trust is a key factor, and numerous operational details around contracting, infrastructure, and data security need to be taken into account. The USSB could act as a trusted broker, helping to streamline the connections between scientific institutions with data and the metascience researchers that can use it.

USSB need not start as a government agency. There is a lot of impact to be had in launching a focused, non-profit, philanthropically-funded effort inspired by institutional efforts like those led by the National Bureau of Economic Research. Such an approach could help prove out the model, building the case and political support for more substantial federal involvement.

Metascience used to be demand-constrained: there simply did not exist a critical mass of researchers and policy audiences focused on these issues. But now we are supply-constrained, by time, money, and data. This last factor may prove to be the most critical.

Thanks to Santi Ruiz and Heidi Williams for their feedback on earlier drafts on this piece.

Is Jay Bhattacharya gaslighting us w/ his "people's NIH" movement?

Why not work with NCSES or ISIS to add a few questions to their existing surveys?